I'd like to take a step back and address something I've brought up here and there in various sermons over the years. It's something that underlies so many issues like fighting terrorism, prisoners in Guantanamo, unchecked government powers, financial bailouts, health care reform, and more. There's no single label for this but it comes up whenever someone asks "How could Democrats support that measure" or "How could Democrats betray their progressive principles and promises like that?"

Not Corruption or Conspiracy

One of the most important things to understand is that we aren't looking at corruption or evil conspiracies — at least, not as we normally understand the terms. Such behavior may at times look superficially like corruption or conspiracy, and the language used to describe it may reinforce that perception, but we must remember that this is not truly the case. This means that solutions to corruption and conspiracies will not work to solve the problems we're facing.

Classic political corruption happens when politicians sell votes or political influence to private interests, thus in a sense privatizing law and politics. When politicians vote in ways consistent with the interests of big campaign donors, that may look like bribery but how else would they vote? How else would groups donate to politicians if not when the politicians vote in ways they like? You only donate to politicians whose votes you support, so are you "bribing" them?

Classic conspiracies involve people meeting in secret to plan for causing harm to others while profiting from it. When members of some group act in ways that benefit themselves at the expense of others, this might look superficially like a conspiracy, but how else would you expect them to behave? Even if some do meet to coordinate their actions, it's not a conspiracy when people act in their own political or economic interests.

Analyzing People's Behavior

So if it's not really corruption or conspiracy that's plaguing us, what's going on?

- People act to secure their most fundamental desires. What people want or need most are the basics: food, water, housing, health, etc. People might be so well off that they can pursue other interests as well, but these will always be most fundamental and you must count on people to pursue them.

- People achieve their most fundamental desires by securing their economic interests. Obviously, you can have reliable access to food and housing when you have reliable access to economic power — i.e., money. Even achieving power over space around you (property) and political power require economic power first. So you make your most fundamental desires more secure by making your economic situation more secure.

- Your economic security is about more than just you. Your economic security is determined not just by your income and assets, but also by the prospects facing the groups you belong to: family, neighborhood, community, race, church, class, etc. No matter how well you think you're doing at the moment, you won't feel very secure if you see lots of people in your family or socioeconomic class doing badly. So whether consciously or not, you'll end up working to not just secure your own economic situation, but also the economic situation of people like yourself.

- Actions speak louder than words. How a person behaves tells you far more about what they really believe than what they say or promise. A corollary of this is that a person's beliefs will, at some point, be reflected in their actions — a belief that never has any impact on behavior isn't much of a belief.

- People generally do what they want to do, given their circumstances. As a general rule we should start with the assumption that any given behavior is actually how that person wants to behave — they believe that it is an appropriate or necessary means for achieving some basic desire. They may be wrong about the means (like playing the lottery instead of learning a trade) and may not even like the means (like a job they hate), but they sincerely believe that it's necessary, appropriate, and/or effective at the moment.

Once we accept these basic premises, it's should no longer be confusing why so many Democrats would support warrantless wiretapping and indefinite detention or oppose a public option for health insurance or greater consumer protection in investments: this is what they really want. People are confused because they assume that politicians want what they — the confused voter — wants but are bizarrely doing the opposite. This would indeed be bizarre, but the fault lies with starting with the wrong assumptions.

To be fair, it's easy to get caught up with incorrect assumptions if we take politicians' words at face value and just believe what they say — or, sometimes, what we read into their words based on our own desires or hopes (sometimes politicians lie outright but sometimes they are simply vague and we fill in the blanks based on what we want to hear). What we should be doing is watching what they do. Remember, their behavior tells us more about their true beliefs and goals than any promises they make.

Politicians who promise often to support something like a public option but then never fight for it and instead start "negotiations" from a very different position did not ever really want a public option. Politicians who complain often about indefinite detention but then don't give up and instead work to make it more firmly established didn't ever really believe that indefinite detention was wrong.

This raises the obvious question of why they would be pursuing one set of policies when voters in their own party strongly support the opposite policies. The answer lies with the first premises: we should assume that the politicians sincerely believe they are pursuing policies which are necessary, appropriate, and/or effective for securing the economic power of themselves and people like themselves. If these policies do not also secure the economic power of the voters because they don't belong to the right groups, well that's just too bad.

Structural vs. Personal

Attributing problems to personal failings rather than to structural defects not only fails to fix the problems, but ultimately ensures that the problems become more securely entrenched. I see this often with religious conservatives, for example attributing racial inequalities to the personal sin of racism and thus solely to the actions of individual racists. They deny that social structures have defects which keep inequality alive regardless of the conscious or unconscious attitudes of individuals.

As a consequence, they oppose making structural changes and instead insist that we just need to get individuals to "repent." Then, if there are no obvious racist motivations, any outcomes will be "just" and "correct." The parallels with the attitudes of so many religious conservatives towards economic inequality are almost exact: a denial that there are any defects in current economic structures combined with an insistence that the outcomes are just — and, sometimes, maybe ordained by God.

Now I think liberals are doing something similar by looking for personal explanations for why some Democrats fail to support a more progressive agenda and even for some of the basic problems that their progressive agenda is supposed to be addressing (banking, health care). This is somewhat understandable because Americans seem to love personal explanations. The culture of Protestantism and individualism focus attention on the individual as a source of change, for good or for ill.

What's more, personal explanations are so much easier than structural ones. It's easy to imagine that if we just "kick the bums out," we'll be OK and everything will be solved. Every time voters are dissatisfied with politics, that's the solution and it never seems to occur to them that it never works. What's that classic definition of "insanity"? I guess it would be more depressing to imagine that the "bums" we have now probably aren't far off from the best we can expect and that they are doing the best we should expect given the political and economic structures they are working in.

Structural solutions are harder to achieve and even harder to imagine. We have grown up with these structures constituting the horizons and boundaries of how we conceive of society being organized. They form bedrock assumptions that we just aren't comfortable questioning — and once willing to question them, it's hard to imaging what else might be worth taking a chance on. If I'm right and our problems are structural, though, that's precisely what we need to do.

Identifying Structural Problems

This matters greatly because it means that people aren't just mistaken about what the problem is, but about the very nature of the problem itself. Corruption is a personal character flaw that can be solved by replacing a corrupt politician with an honest politician. Conspiracy is a personal character flaw that can be solved by catching the conspirators and replacing them. Even mere confusion on the part of the politician is a personal, individual problem which can be solved if we reason with them and get them to "see the light" — to realize that their behavior contradicts their previously stated goals.

None of these approach will work for us, though, because the actual problems facing us are more structural than personal. You may have noticed that none of the principles of behavior that I describe above are immoral. That's because they are basic, expected facts of human nature — there's nothing inherently moral or immoral about them. They are like breathing. They can, however, be turned towards moral or immoral ends and that's where the social structures of society come into play.

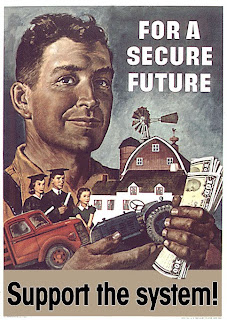

Our economic, political, and social structures have made it a virtue to exploit the weak. It's not corruption to look out for our own economic interests and to try to achieve economic security, but it's a structural problem if such behavior is allowed to undermine the basic interests of others. It's a structural problem when securing our economic future depends on reinforcing a system that undermines the economic security of others.

Weighing Structural Solutions

If we do accept that our problems are structural and thus won't be solved simply by replacing a few annoying politicians, just how far will we be willing to go to solve them? Just how deep into our social, political, and economic structures will we go to try to fix things? Tactics range from just tinkering around the edges in order to preserve but improve the current structures to razing them down to the foundation and constructing something new.

In most of the cases where someone recognizes that our problems are more structural than personal, they are probably arguing for the former: tinkering around the edges. A great example of this, and certainly a very relevant one right now, would be the proposals for health care and health insurance reform. Most are just tinkering around the edges because they involve modifications to the existing structure in order to reduce the harm it causes — and this they would certainly do. Elimining "recission" would reduce a lot of harm, but it wouldn't affect how health insurance and health care are provided.

A single-payer insurance plan, in contrast, would change the underlying structure by eliminating a primary source of the harms: the profit motive in providing basic health care. A single-payer insurance plan would fundamentally alter the means by with health care is provided and health insurance is managed. This is not to say that it be problem-free, but it would be free of a primary cause of the harms which most reformers are trying to fix by tinkering to address the symptoms.

Now, I'm not making a blanket condemnation of "tinkering" and a blanket recommendation for "restructuring." Sometimes, despite the harm caused by a system, it's clear that all other systems would be worse. There are lots of problems with democracy, but all the other ways of structuring political power are worse, so "tinkering" is definitely the best means for dealing with its problems (though some "tinkering" can be fundamental — for example, America moving to a parliamentary system would not be perceived as mere tinkering even though it wouldn't be changing the more basic democratic structure).

I do think, though, that too few people are willing to even consider that our problems are structural, even fewer are willing to engage in substantive structural critiques of the systems we take for granted, and fewer still are willing to propose or support significant structural changes that would fundamentally alter political, economic, and power relations in society. Since people need to learn to walk before they can run, we need to start first with getting people to consider structural sources for their problems and critiques of those structures. Even if a structural solution isn't the way to go, people will at least be prepared with more substantive "tinkering."

Mr. Cline, Sir,

ReplyDeleteNow you've done it. I posted this response to the CNN blog Survey: Most Americans believe government broken.

If Americans can agree that there is a serious problem in America, as an outsider (Canadian), could I make an observation?

There are two major sources of malaise as I see it. First, the structure of your government is routinely deadlocked, so much so that most serious issues eventually are off-loaded onto the judiciary to be resolved, or at least dealt with.

This is grossly inefficient, and very expensive. What if instead of having a House of Reps voted in for 2 years, they were voted in for 4 or 5, so they wouldn't be spending their whole term looking over their shoulders at the next election and worrying about election financing (and the lobbyists), and consequently not getting a lot of government work done?

And the Senate; what if instead of having them elected and so justified in dismissing the House of Representatives bills, they were instead appointed, perhaps by a Presidential committee, to serve as a jury charged with vetting government proposed legislation in committees, holding hearings? While they can send legislation back to the government with important amendments, they are NOT allowed to dismiss it based on party politics.

If these government changes don't seem to make a difference, please believe they do. This is largely what we have, and it works terrifically. Yes, there are still some bugs, and I'm not advocating 'the Canadian system', but America may want to reconsider what they have at present.

The second source ot the American malaise, has to do with two lines out of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, specifically:

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" and

... freedom to bear arms.

Together, these two lines combine to produce an ugly directive to hand a nation: grab much to much, or you'll get nothing at all (K. Vonnegut), and once having done so, feel free to defend yourself with deadly force. Paraphrased, Grab and Defend.

I suspect that your founding fathers didn't intend to send this message, and perhaps the strong puritanical morals of the people at the time of the Philadelphia Convention, were strongly underpinned by Christ's teachings of brotherly love. Perhaps that's why the moral majority defer to Christ even to this day. The problem is that the rest of the nation isn't buying it anymore.

What I'm suggesting by revisiting both the structure of the government and the American articles of incorporation, is that America may need to revisit 1787 and the Philadelphia Convention.

This is a classical Marxist analysis. I have many problems with Marxism, but "People achieve their most fundamental desires by securing their economic interests" will suffice for now.

ReplyDeleteNo, they don't. How does the abortion debate relate to anybody's economic interests? How about suicide bombers? Are they, like Willie Loman, "worth more dead than alive"?

No, they don't.

ReplyDeleteThen how do they?

How does the abortion debate relate to anybody's economic interests?

In lots of ways: people may want an abortion or not want an abortion for reasons that are at least partially economic. Some people need more kids for economic reasons. Some people don't want more kids for economic reasons.

More importantly, though, if preserving legal abortion of making abortion criminal is regarded by someone as a fundamental desire, or a step on the path towards a fundamental desire, then they will need time and money. Both require some measure of economic security.

How about suicide bombers? Are they, like Willie Loman, "worth more dead than alive"?

Suicide bombers need bombs and the material for bombs needs to be obtained somehow. Timothy McVeigh had to secure his economic interests to some degree in order to be able to afford to make his purchases.

"Then how do they?"

ReplyDeleteSorry, not going there. Not qualified. I have my hands full defending the notion that a pure Marxist analysis of political motivation is insufficient; I don't have to replace it with one of my own.

"reasons that are at least partially economic"

c'mon. Seriously? Can you split that hair any finer?

I've been reading your stuff for awhile. You're better than this.

"making abortion criminal is regarded by someone as a fundamental desire, or a step on the path towards a fundamental desire, then they will need time and money."

Disingenuous. Has nothing to do with your original claim. Why do they consider it a worthwhile investment of time and money? Your original post treated economic interests as a fundamental end. Now they are a means?

Cliney-whiney, I tried to read all of this and make sense of it, but it was too long. It's bad enough that you somehow manage to regularly befoul this conservative thoughtspace with your leftist maunderings, but must you hog so much bandwidth to do it?

ReplyDeleteI would like to address specific criticisms of your latest libboscreed at a deeply meaningful level like Donovan Digital has, but that would require me to have read your entire piece and comprehended it. But it's Sunday morning and, for several reasons, my brain is not capable of that. Perhaps after church...

I will say one thing I noticed, though -- you mention generic "politicians" who appear to favour communistic things like giving health care to all Americans, and who pretend to oppose patriotic policies such as allowing the president to imprison anyone forever without any trial, if the president's men deem that person is a terrrrrrrrist. You're afraid to use the "O" word, aren't you Cline?

OBAMA is doing that! Not unnamed "politicians" but OBAMA! Hurts, doesn't it, to know that your liberalord and saviour is actually on the side of conservatives (and therefore, the side of G*D!) when it comes to how he acts, eh?

Getting back to your original thesis, Obama is acting in HIS best interests to join with the all-powerful conservatives. At the most basic level, it means that he does not get assassinated, or that nothing bad happens to his wife or little daughters. Wouldn't want a massive natural gas explosion -- accidental, of course -- to level their fancy private school and mebbe a couple city blocks around it, would we? This tends to happen to people like Paul Wellstone who oppose Americanastiness, doesn't it?

Your King Obama also realizes that if he goes along with patriotism like outlawing abortion via presidential signing statements, he stands a better chance of being rewarded with richness once he's thrown out of office. Who would you rather be, Cline, a Bill Clinton or Jimmuh Carter, who has to go around building houses with his bare hands like he's some sort of wandering carpenter in Roman-era Judea? That's the reason I vocally support conservatism -- because I'm sure the riches will eventually roll down from the top and bestow their blessing on my bank account.

I'd taunt you more, but I don't want to echo your sin of long-windedness...

If I were a member of Congress, which I'll never be but go with me here, I'd propose a lot of legislation that I knew would never pass but that would make headlines and I'd do this to mock the implicit culture of the federal legislature.

ReplyDeleteAn act requiring members of congress to cut off a finger every time they're caught violating one of their major campaign promises.

An act requiring members of congress to subject themselves for a public demonstration of interrogation techniques.

An act requiring Senators to surrender all their wealth to the state and take a vow of poverty for the duration of their tenure in the Senate.

None of them would pass and I'd probably be censured for wasting the Congress's time, but my point would be made.

Sorry, not going there.

ReplyDeleteSo you're going to deny that people achieve fundamental desires by securing economic interests, but you're not going to trouble yourself to suggest any other means that they might use.

That's you're right, of course, but it makes any critiques you offer unworthy of much time or attention.

Can you split that hair any finer?

I'm not "splitting" anything. I'm simply pointing out the fact that there are economic interests connected to abortion.

I've been reading your stuff for awhile. You're better than this.

I also have enough on my plate that I don't need to waste time with a person who isn't interested in a serious, substantive conversation.

Disingenuous. Has nothing to do with your original claim.

It is, in fact, exactly my original claim: people need economic security in order to secure basic desires.

Why do they consider it a worthwhile investment of time and money?

When "it" is a fundamental desire, it wouldn't be worth investing time and money if it weren't a desire.

Your original post treated economic interests as a fundamental end.

No, it didn't.

Now they are a means?

Of course they are. You even quoted the statement which made it clear that they are a means: "People achieve their most fundamental desires by securing their economic interests."

What's the goal? Fundamental desires. What's the means? Securing economic interests. If I had written "people achieve happiness by walking in the park," would you have concluded that I regard "walking in the park" as the end rather than the means?

If such basic English is beyond your ability, maybe you should find something to do besides reading blogs.

Jeez, I spend the day watching NCAA basketball and tweeting about healthcare reform and you people get into an argument without me!

ReplyDelete無尾熊可愛 said...

ReplyDeleteI do like ur article~!!! .....................................

And here we see the type of robot who likes Cline's writing!

Fundamental change to the structure itself? I'm all for it. That's why I'm an anarchist. Voting people in power who promise "change" has proven to change nothing.

ReplyDeleteAs insufferably self-serving as much of Libertarian philosophy is, this is perhaps its only redeeming quality: Libertarians are prepared to accept a BIG change in America.

ReplyDeleteWhile Republican America doesn't want change because it may compromise their privileges, and Democrats wax reminiscently about America's nobility and grandeur despite some 'operational problems', it's only the Libertarians that are so disenfranchised that they'd sooner see the whole thing tossed.

For this reason, they call themselves anarchists, which isn't actually true because only the psychotically ill would seriously want to see anarchy.