Help Me Reach 12 on the Manly Scale of Absolute Gender

If you like the patriotic work we're doing, please consider donating a few dollars. We could use it. (if asked for my email, use "gen.jc.christian@gmail.com.")Thanks!

Sunday, December 24, 2006

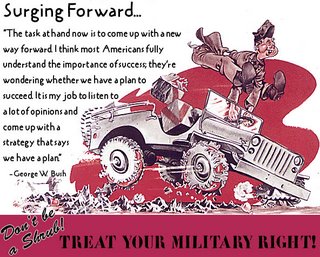

Surging Forward: Debating American Troop Levels in Iraq

Posted by

Austin Cline

There is a lot of public discussion about whether America should increase troop levels in Iraq, either temporarily or for the long term. There are a number of forceful voices on both sides and the very existence of this debate is healthy — can you imagine a similar disagreement proceeding so publicly and strongly even just a year ago? For far too long, public discussions have been little more than a mockery of how debates should proceed in a democracy — Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum pretending to disagree when they have already accepted the same policy positions and are just haggling over the details of implementation for the sake of public theater.

Perhaps the current debate isn’t much better in some ways because most of the ground being covered is simply whether to increase troops and for how long, not whether the entire policy is a failure and should be fundamentally altered, but at least that is being touched upon around the margins. It’s not where we should be, but it’s a refreshing change for the better, and if it’s still poor then that simply reinforces how bad things have been.

So, what should happen with troop levels in Iraq? Most liberal critics seem to react almost instinctively to condemn the idea, but I think that we should be more willing give temporary increases serious consideration. There are of course questions about whether increases are even feasible from a logistical perspective — we don’t want to ruin the military for the sake of trying to achieve a temporary gain, after all.

I’m trying to address this from a perspective of what the appropriate policy should be, though, and at least in theory there could be valid reasons for temporary increases, though they don’t seem likely to exist in reality. For example, an increase might be needed to deal with a sudden crisis, to press home a new advantage that has opened up, or even to help structure a large-scale withdrawal of troops overall.

There is one feature which such situations should all have in common: a reasonably clear goal that creates a definite picture of what “success” would look like, such that we have an idea not only of what the troops are trying to achieve, but also of when they will return once they have achieved it. Doesn’t that sound like the conditions that should have been in place before any troops were sent in at all? We didn’t have them then, and we are unlikely to have them now — that’s why valid reasons for a “surge” may be theoretically possible, but probably won’t be forthcoming.

Of course, there’s no point of even pretending to have a debate if neither the course it takes nor its final outcome will have any impact on the ultimate decision — but that’s precisely what we are probably facing. President George W. Bush has declared himself to be the “decider,” and there is little evidence that he takes seriously advice or warnings from people who tell him things he doesn’t want to hear.

He seems much more likely to listen to advice when people are telling him things that justify the choices he already intends to follow. Any surge in troops will simply be part of “surging” forward with the same basic goals that have existed since the beginning. Bush isn’t looking for a plan — he’s looking for new ways to get people to believe that he has one in the first place. It’s all about selling his war to an increasingly skeptical public, not about developing the best means for pursuing a necessary conflict as part of a defensible agenda.

Bush has said in the past that he opposed politicizing the war (a process he observed with Vietnam) and intended to follow the advice of his military commanders; today, he appears poised to reject the recommendations of his military commanders who don’t want more troops sent in. Bush is wrong on both counts: every war is necessarily political and all decisions must be made on the basis of both political and military needs. Sometimes the former will take precedence over the latter, and only under a military dictatorship do the military commanders make all of those decisions.

On the other hand, sending in more troops against the wishes of military commanders is probably a bad idea anyway if they are saying it won’t help the situation and may hurt the military overall. Even if Bush has the right idea about how political leaders must make decisions about how to pursue a military conflict, he seems to have chosen just about the worst time to assert that role and reject the advice of military commanders.

Political leaders may make militarily poor decisions that we don’t like, but they, not the generals, are elected by and accountable to the people — including the troops being put in harm’s way — and thus the final decision must be theirs. Bush is in charge and has a responsibility to make military decisions on the basis of both military and political factors. We the people, however, have a right know what those factors are and why they are being used. We have a right to know why he would continue with the same policies and plans despite how they are shredding both military lives and the nation’s military capability.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

We'll try dumping haloscan and see how it works.