One of the best ways of controlling dissent may be to ensure that it never has a chance to develop in the first place. This can be achieved by preventing people from obtaining information that is contrary to state policies and agendas - if they only know what you want them to know, they are more likely to support the policies you are pushing.

In Hitler's Justice: The Courts of the Third Reich, Ingo Muller describes how some of this played out in Nazi Germany during World War II. One of the most significant laws was the "Extraordinary Measures Related to Broadcasting" which made it a crime, punishable by time in prison, to listen to foreign radio broadcasts. People who listened and passed information along to others were accused of undermining "the capacity of the German people to resist" and could be sentenced to death:

In one such case, a Special Court acquitted a landowner who had informed one of his hired hands on March 27, 1941, that the government of Yugoslavia had been overthrown after joining the so-called Triple Pact (signed by Italy, Japan, and Germany) on March 25 in Vienna. This piece of news was broadcast throughout the Reich itself during the evening hours of March 27, but the defendant had heard it shortly before on a Swiss radio station. The Special Court was of the opinion that the report was not likely to threaten the capacity of the German people to resist, since it was not only accurate, but broadcast only a few hours later in Germany as well and was not unexpected, as the internal political difficulties of the Yugoslavian government had been well known when the pact was signed.

The Fourth Criminal Panel of the Supreme Court nevertheless reversed this acquittal and demanded a penitentiary sentence. The justices determined that for the defendant to be found guilty it was not necessary for "damage to have occurred or for there to have been a particularly negative effect or even for resistance to have in fact been weakened. The likelihood or threat referred to in the decree is inherently present in all news which . . . in its content can be detrimental to the German people in their vital struggle. . . The time and form for making unfavorable news known must be left to the authorities. The fact that the news is later made known by German sources. . . does not render an act which has already been committed exempt from punishment."

The premise behind this decision is that people don't have a right to information, and in particular to information that is unfavorable to the government's plans. Instead, the government has the authority to determine which information people deserve to know and which should be kept from them — including information which might affect them.

This might sound like something that would only happen in an authoritarian society, but even in America we have people who think in similar lines. There are no bans on listening to or spreading information from foreign news services, but there are attacks on American media who broadcast information that the government wants to keep secret — including information, like domestic spying, which might affect you directly. Once again, the premise is that you don't have a right to learn what the government might be doing to you or in your name.

Franz Vollmer, a senior official in the Ministry of Justice, included in his summary of judicial decisions for 1943-1944 a whole catalogue of remarks which now ranked as capital crimes:

"Not to be tolerated and as a general principle deserving of the death penalty... are remarks of the following kind: the war is lost; Germany or the Führer started the war frivolously or to no purpose, and ought to lose it; the Nazi party should or would resign and clear the way for peace negotiations, as the Italians have done; a military dictatorship ought to be established and would be able to make peace; people ought to work more slowly, so as to bring an end to the war; the spread of Bolschevism would not be so bad as the propaganda makes out, and would harm only leading Nazis; the British or Americans would stop the Bolsheviks at the German border; verbal propaganda or letters to the front urging soldiers to throwaway their guns point them at their own officers; saying that the Führer is sick, incapable, a butcher of men, and so on."

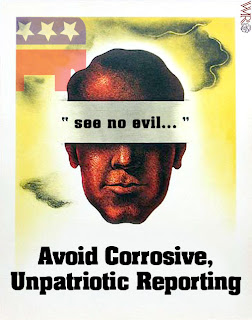

There are certain similarities between this and something said by Karl Rove in 2006: "It's odd to me that most of these critics are journalists and columnists. Perhaps they don't like sharing the field of play. Perhaps they want to draw attention away from the corrosive role their coverage has played focusing attention on process and not substance."

Here, "corrosive" refers to the ways in which the free press has directed criticism and doubt towards the Bush administration. One of the most disturbing themes repeated so often by the Christian Right in America has been the idea that distrust of the government and dissent from the administration qualifies as a lack of patriotism — or even a sign that one is on the side of the enemies.

There is a significant amount of insecurity behind such attitudes — both on the part of those in power, trying to avoid critical scrutiny, and those out of power who are trying to provide justifications for why the powerful shouldn’t be scrutinized more closely. We should care about the early signs and examples of such attitudes because the direction they lead to is a place none of us want to go.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We'll try dumping haloscan and see how it works.